Top People |

| Men's Singles Champion |

R A Algie (A) |

| Women's Singles Champion |

Miss J M Williamson (C) |

Ranking List |

Men

- R A Algie (A)

- R V Jackson (A)

- W O Jaine (A)

- W J Fogarty (O)

- K F Dwyer (A)

- V N Brightwell (O)

- Albert Kwok (O)

- M L Dunn (W)

- J S Crossley (W)

- B D P Williamson (C)

Women

- Miss J M Williamson (C)

- Miss M M Hoar (WR)

- Miss J E Leathley (O)

- Mrs D J Chapman (O)

- Miss E McNeill (HV)

- Miss M McLennan (O)

- Miss A M Hughes (W)

- Mrs E A Collins (SC)

- Miss B I Powell (SC)

- Miss P M Quinn (C)

|

| Executive Committee |

| V M Mitchell (Chair), H A Pyle

(Deputy Chair), K B Longmore, W Mullins, T S Williams, J C McCluskey, A E

Carncross, P Dudley, A R Algie, K C Wilkinson (Secretary),

H N Ballinger (Treasurer). |

|

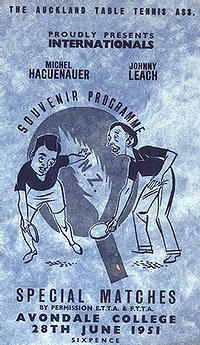

World

Champion Visits New Zealand

We’ve had world champions here before (Perry, Szabados, Barna and Bergmann), but none

of them were reigning champions. Bergmann came the closest, losing his title only

seven months before his visit and poised to win it back five months after. Laszlo Bellak

was the current world mixed doubles title-holder when he visited in 1938 but as 1951

dawned we still awaited our first visit from a reigning singles world champion.

The wait ended on 6 June when Johnny Leach touched down in Wellington

Harbour at the end of a long flying boat journey from Singapore via Sydney.

Leach’s ascendency to the status of world conqueror had been rapid and spectacular.

It began during his war service with the RAF. He was on 24 hour shifts and would often

stay up for most of his 24 hours off and practise pushing the ball to various parts of the

table simply to develop ball control. By war’s end he was a classic all-rounder: long

range defence, attack on both wings, the drop-shot – he’d mastered them all. But

many saw his skills spread too widely and thinly to take him to the top. Renowned English

coach Jack Carrington disagreed. He took the 22 year old under his wing,

urged him to hit the ball harder, move his feet quicker, and believe he could beat anyone

in the world. By 1946 Leach had a world ranking, reached the world semi-finals in 1947 and

became world champion in 1949. He lost narrowly in 1950 to Frenchman Michel Haguenauer in

the semi-final, and regained the crown in 1951.

The complex negotiations leading up to Leach’s visit is summarised in a 1950 article.

He had already travelled extensively and Richard Bergmann influenced him to include New

Zealand in his latest trip. Bergmann’s memory of his own experience here in 1949 was

still vivid.

Michel Haguenauer (35) accompanied the now 28 year old Leach on the four

week New Zealand tour. While Haguenauer was destined never to win a world title he was

still a world class player and able to match the champion in their series of exhibition

contests. Unlike some previous exhibitions these were highly competitive – both were

out to win. Leach won a narrow majority but the spectacle was warmly received wherever

they played and regardless of who won. Haguenauer was, like Leach, a skilled all rounder

but with a ferocious forehand and a chop defence played closer to the table than

Leach’s long-range floating returns. Leach was more of a stylist with impeccable

footwork, Haguenauer (six foot two and fourteen stone) more spectacular but a little

ungainly. He played with a “hammer” grip (no finger on the blade) while Leach

used two fingers for extra control. They made less use of spin than our last international

visitors, Barna and Bergmann in 1949.

They were a popular pair – Haguenauer’s hearty laugh became familiar to those

who travelled with him, and Leach’s more reserved good humour was often on display on

the table.

They played fourteen provincial contests with the not too surprising result of fourteen

wins, all to nil. Johnny Leach was clearly going easy on his lesser opponents, but this

was to his cost in his first match against Wellington. John Crossley beat

him 21-18 in the first game. Seeing that game slip away Leach knuckled down in the latter

stages but Crossley, remembering his international success in Scotland the previous year,

rallied brilliantly and held on to win. Leach won the next three 21-8, 21-9, 21-10. No

other games, singles or doubles, were dropped by the touring pair on the tour.

Among the lighter moments were Leach’s 11 point games with local players using a tiny

two-inch wide bat, and his practice of occasionally playing out of turn in mixed doubles

if a shot looked a bit difficult for his local partner to deal with.

“Test” Matches

These could hardly be defined as tests – the players in the opposing team were from

two different countries. But it was deemed a New Zealand test team and competition for

selection was intense. There were grumblings over the scheduling. Only two tests were

played, and on successive nights. Provided selection was based on merit, this meant the

same players would play in both and no others had a chance to play their way in. But the

schedule was tight and couldn’t be changed. Selection was indeed based on merit and

chosen for the singles were NZ champion Bob Jackson and (back from “retirement”

– refer below) Russell Algie! John Crossley and Neville

Brightwell were selected for the doubles.

Jackson had already been exposed to the tourists in the Auckland match and it hadn’t

been a good start to his international career. He had begun nervously and even when he was

able to execute one of his favourite shots with precision (the drop shot) he could only

stand and watch while Johnny Leach raced in and put it away for a winner. This severely

dented his confidence.

In the first test in Wellington he and Algie played a little more freely but the

score-sheet still made sorry reading with an abundance of single figures. Crossley and

Brightwell did rather better in the doubles, 13-21, 13-21, 15-21. Improved scores were

registered in the second test in Auckland.

Prior to the test matches Christchurch had hosted a contest featuring an all-New Zealand

selection (John Crossley, Neville Brightwell, Laurie Wilson and

Pat Spillane) with all four playing singles and doubles against the international

tourists in front of a crowd of 1,200 at the Civic Theatre.

Representing the North Island, Algie and Jackson faced the tourists once more in the final

contest of the tour in Hamilton. Owen Jaine joined Algie for the doubles.

All the New Zealand players, national and provincial, did their best. But it was never

going to be good enough.

Leach and Haguenauer Assess NZ Table Tennis

The New Zealanders lucky enough to face Johnny Leach and Michel Haguenauer on their 26 day

tour were all beaten by faster footwork (attack and defence) and superior anticipation,

ball control, consistency, concentration and experience (13 world championships for

Haguenauer, 5 for Leach). When asked his honest opinion on the standard of table tennis in

New Zealand compared to other countries he had visited, Johnny Leach said that even our

best players were well below world standard. “The stroke play of New Zealanders is

quite good,” he said. “What is lacking is footwork, concentration and the sheer

will to do better.” He stressed that stroke play without tactical skills can’t

win matches at top level.

Michel Haguenauer added the comment that New Zealand players are too anxious to win the

point quickly rather than tactically, and if necessary patiently, work towards an opening

for the kill shot. Both urged New Zealand to import a professional coach, and to expose

New Zealand players more often to international competition.

Leach considered John Crossley our best player, followed by Russell

Algie and Bob Jackson with Neville Brightwell

not far behind. He thought Trevor Flint had made an impression overseas

(refer below) but like many others in New Zealand, would benefit from professional

coaching. Andy Wong, who played singles alongside Jackson in the Auckland

contest, was named as the country’s most promising young player.

New Zealand farewelled the popular duo on 1 July. The tour had been financially

profitable, had given our top players and administrators plenty to think about and,

through generous media coverage, had considerably boosted the public image of the sport in

this country.

Even more popular visitors would arrive in 1953.

New Zealand Team at World Championships - Again

Following what was now becoming a well-worn path, three more New Zealanders made their way

by sea to Europe to participate in the World Championships. Russell Algie

had shown the way in 1948 followed by John Stewart, John Crossley and

Neville Brightwell in 1950. Even as the 1950 trio were still voyaging back to New

Zealand mid-year, Jack Borough was investigating the availability of

positions for himself and Trevor Flint on the crew of any vessel making

its way to England later in the year. He was determined that they would find their way to

Vienna, Austria in time for the 1951 championships, accompanied by a third person and

competing as a New Zealand team in the Swaythling Cup competition.

A number of players were approached to complete the team but were unavailable. Eventually

Hutt Valley representative Jack Knowlsey agreed to travel and all three

began an anxious wait for a job opportunity on a ship. Feeling they were running out of

time, Borough and Flint opted to travel as paying passengers on the Rangitata

while Knowsley continued to wait for a crewman’s position. He had been leaving home

each morning packed for the trip, waited around the gangways at the wharf all day and

returned home without success every day for three weeks. A day or two after Borough and

Flint’s departure he finally secured a steward’s position on the Taranaki

and sailed off in the wake of the Rangitata.

They arrived in England a good three months before the world championships. Under the

guiding hand of New Zealand’s man in London (the ever-reliable Corti Woodcock) and

assisted by coach Jack Carrington, the three were introduced to a London club (St Bridges)

and entered a succession of tournaments ranging from club championships to the English,

Welsh and French Open.

The team was considered to be slightly below the standard of the Stewart / Crossley /

Brightwell combination but managed to register fairly similar results. Trevor Flint was

the most consistent and the most successful. He reached the second round of the English

Open and round three in the Welsh Open. At a huge Central London tournament (291 in the

men’s singles alone) Jack Knowsley reached the mixed doubles

semi-final. By the end of the build-up period, all three felt they were playing several

points better than when they left New Zealand.

They supplemented their financial resources, and maintained their fitness, by taking on

casual work as council employees.

Outplayed at World Championships

They travelled from England to Vienna under no illusions. Any contest win in the team

events or single match in the individuals would be an achievement to treasure for a

life-time. The hard reality is that they lost heavily to France, South Vietnam, Hungary,

The Netherlands, Germany and Austria. Their moment of glory all but came in a contest

against Portugal which they lost 4-5. It was unfortunate that Jack Borough had

to play the deciding singles at 4-4 with an injured shoulder.

Trevor Flint scored 19, 19 and 17 against a top French player in the

first round of the individual singles – New Zealand’s best performance. Flint

has a strong chop defence and lightning attacking strokes down either wing. He was to

become one of New Zealand’s top players on his eventual return.

The individual events were a triumph for England. Johnny Leach reclaimed

the men’s singles title he had won in 1949, and a pair of identical twins –

Rosalind and Diane Rowe (17) sensationally won the women’s

doubles in a spectacular final.

Lessons Learned

The party split up for the voyage back to New Zealand. Jack Borough returned immediately

after the championships, Jack Knowsley about a month later and Trevor Flint remained in

London for the rest of the year for business reasons. As the main instigator of the trip,

Jack Borough communicated with the NZ media and his thoughts were widely reported. He felt

a major disadvantage in New Zealand was lack of top level match play. “Top players in

England get more chances to play against better overseas players in one season than New

Zealanders would get in seven,” he wrote. Trevor Flint later added that many English

players practised six nights a week for eight months of the year. All three noticed a vast

difference in the speed of the tables in Europe – they were much faster, especially

in England.

The trip by the three adventurous New Zealanders gave officials another chance to

re-assess our position in the world, and to examine our priorities. A major controversy

arose over which should come first – engaging an international coach, or financing a

trip to the next world championships by an officially selected team. The next article

deals with that debate.

Professional Coach, or 1952 World Championships?

An issue which occupied the entire year and stirred a high degree of

emotion and parochialism was an AGM decision to select and finance a team of three men and

a manager to attend the 1952 World Championships in Bombay, India.

Doubt was expressed at the meeting over whether this was the best way to spend such a

large amount of money, hard-earned cash from the pockets of grass-roots players. Wanganui

Association led the opposition by moving an amendment to the original proposal

allowing more flexibility - only go to Bombay if NZTTA considers the money in hand is not

needed to assist the game and affiliated Associations within New Zealand. The mover of the

amendment (Morrie Gordon) included in his statement of case a suggested

alternative use of roughly the same amount of money - engage a professional coach to tour

New Zealand for six months.

The arguments on both sides were well aired and would be thrashed out again on two further

occasions. Those favouring the World Championships believed the benefits of international

competition would filter right through to grass roots players. And this was a great chance

to get to the Worlds for a lesser cost – they were usually played in Europe and it

could be a long time before they were held in Asia again. Those favouring the alternative

claimed that direct contact with players at all levels by a professional coach would be

better value for money.

The Wanganui amendment was put to the vote and narrowly defeated. The original motion was

then carried, again narrowly. The trip was on.

Problems arose immediately. Financial support from Associations was essential and they had

already been asked whether, if the trip went ahead, they would agree to contribute to the

cost of air travel, or sea travel? Not surprisingly, the majority favoured the cheaper sea

option. But when leading players were approached regarding their availability (if

selected), every one of them said they would only travel by air.

The issue was resolved by the launch of an art union (raffle, lottery), large enough to

raise a £1,600 contribution to the air fare. Most Associations agreed to support it.

Meanwhile the management committee was formulating selection policy and decided by a

narrow majority that the three best men would be selected. No young developing player was

to be included.

What About the Women?

Then came a further complication: a strong argument was put forward (in the press and

elsewhere) for a women’s team to be sent rather than a men’s. The AGM had

decided on a men’s team but the decision could be overturned. It was suggested that Margaret

Hoar, June Leathley and Joyce Williamson could be approached.

This was not followed through and the idea of changing the team from men to women came to

nothing. But a rapidly improving 20 year old from Wellington, Pam Smith,

took the initiative and embarked on plans to assemble a team of three women to accompany

the men by paying their own way.

About Face

The Bombay / Professional Coach debate did not lie down. It was re-activated, again by

Wanganui (with support from North and South Taranaki) at the New Zealand Championships.

Notice was given of a Special General Meeting on the evening before the finals to consider

applying the money raised by the art union to the engagement of a professional coach. Jack

Carrington, who had trained Johnny Leach, was named as the preferred person with Richard

Bergmann second choice.

Many of the same arguments were presented again but this time the decision went the other

way. The motion to cancel the trip and engage a coach was passed by 54 votes to 38.

Neither Carrington nor Bergmann were available so there would have to be a search for an

alternative.

Bombay Bombshell

On hearing the trip to Bombay was now cancelled the leading players were devastated. They

had played their hearts out at the NZ Championships under the impression that a good

performance could earn them selection. The four men’s semi-finalists, all from

Auckland, were particularly angry with their own Association. Auckland had voted to call

off the trip but only 20 clubs out of 59 had attended the meeting which made that

decision. “I know of at least three clubs that were not even advised of the

meeting,” complained Owen Jaine. If Auckland had cast its ten votes

the other way the trip would have been saved.

Rumours that the four considered boycotting the semi-finals and finals as a protest are

confused and contradictory. Newspapers blazed headlines such as “Table Tennis Men

Threaten Strike” but a later NZTTA enquiry found that the rumours arose from the late

arrival of three players who were legitimately delayed by the cancellation of a bus

service.

One More Attempt

There was a final attempt to rescue the Bombay trip. Otago Association, with the support

of Wellington, Canterbury and Marlborough, called for yet another special meeting in

November, proposing the restoration of the original AGM decision. The motion was narrowly

defeated.

Wellington, strong supporters of the trip, blamed what they saw as a seriously flawed

voting system. No Association could exercise more than ten votes regardless of its size.

“Associations with a total of 705 interclub teams were able to outvote those totaling

1,089,” fumed an angry Tommy Williams on hearing the result.

By and large, commentary in the press favoured the trip throughout the debate. Considering

they had been writing about it, recommending it and anticipating it since late 1950 this

was unsurprising. But after the November meeting there was no going back. New Zealand

would not be attending the Bombay World Championships. With the help of Corti Woodcock in

London applications for a six-month tour of duty in New Zealand were sought from

professional English coaches. Six were received and Woodcock recommended Ken

Stanley – a person unknown in New Zealand. He was scheduled to arrive on 1

April, 1952.

The divisions created by the year-long controversy were deep and slow to heal.

|

World

Championships Decision Spoils Mixed Doubles Plans

Two male players, one a top New Zealander and the other a former World Champion, developed

an interest in whether or not a NZ women’s team competed at the 1952 World

Championships alongside the men – assuming at that point that the men would in fact

be going. Russell Algie had been involved in coaching in 1950 and his

students included a promising young player, Barbara Williams. She

improved to such an extent that he encouraged her to enter the Auckland Championships even

though she had no experience of competitive table tennis, not even interclub. She won the

women’s singles! It was such a remarkable debut that plans were made for her join Pam

Smith and Charlotte Savage, currently training at the Michael

Szabados academy in Sydney and hoping to enter the 1952 World Championships as a New

Zealand team, travelling with the men. Algie had already decided that, if Miss Williams

did travel, they would play the world mixed doubles together. A similar plan was afoot in

Australia. Michael Szabados was coaching 20 year old Pam Smith

who had moved to Sydney from Wellington to improve her game under his tuition. He was keen

to play the world mixed doubles with her if she made the trip.

But in a disappointing anticlimax the women chose not to pursue the possibility of

competing at the World Championships once the decision was made to cancel the men’s

trip. The chance was lost and it would be another six years before the first New Zealand

woman competed at world level.

Welcome Back, Algie

The decision (short-lived as it was) to select a team based on merit for the 1952 World

Championships in Bombay was a major factor in Russell Algie’s

decision to come out of “retirement”. He declared last year that his top level

playing career was over and was conspicuously absent from the 1950 NZ Championships. But

in May this year he made himself available for Auckland interclub and quickly returned to

form. His almost certain selection for Bombay, his work with Barbara Williams

(pictured)  and the prospect of playing doubles with her at the World

Championships kept his enthusiasm bubbling. He eagerly anticipated the New Zealand

Championships and the announcement of the team. and the prospect of playing doubles with her at the World

Championships kept his enthusiasm bubbling. He eagerly anticipated the New Zealand

Championships and the announcement of the team.

By the time the Championships drew near, pundits were busy predicting which three men

would be selected. Algie was at the top of everybody’s list.

NZ Championships: All eyes on Algie, Jackson, Hoar and Leathley

New Zealand table tennis fans never got to see an Algie / Cantlay men’s final in the

1940s. The question at the Wairarapa-hosted NZ Championships in 1951 was whether they

would get to see an Algie / Jackson final – and if so, who would win? They had also

seen two consecutive Hoar / Leathley women’s finals and the same pair were seeded one

and two this year. Would they meet again - and if so, who would win?

Joyce Williamson had other ideas. The 16 year old was seeded 5th but

spared an encounter with second seed June Leathley thanks to a

giant-killing performance by unseeded Ellen McNeill who beat the twice

runner-up three straight. This left Williamson the task of dealing with a fired-up McNeill

in the semi-final. It went to five, but Williamson won. When she faced Margaret

Hoar in the final she was a warm favourite, having beaten her in the Wairarapa /

Canterbury inter-Association contest. Despite her reputation for saving her best for the

big matches, and generous support from her Masterton home crowd, Hoar’s defence was

simply not good enough for Williamson’s confident and consistent attack. It was a

spectacular match, won three straight by Williamson and bringing Margaret Hoar’s

three year winning streak to an end.

The win by the young Canterbury star put her in the record books as New Zealand’s

youngest champion. For Margaret Hoar, it was a mere blip in her career. Much success was

still to come.

The men’s giant killer was Kevin Dwyer. He beat, first, John

Crossley (4th seed) and then 6th seed Neville Brightwell. He was

rewarded with a semi-final berth where he found Russell Algie’s

defence too impenetrable. Bob Jackson won the other semi-final, helped by

an error-ridden Owen Jaine.

A shadow was cast over these semi-finals. They were played after the four had just learned

to their disappointment that a trip to the World Championships for a team of three men had

been cancelled (refer earlier article).

Only a purist would define the much-anticipated Algie / Jackson final as a spectacular

match. Algie won in four games after a dour (but delicately tactical) 51 minute cat and

mouse struggle with both players attempting to outwit the other with cleverly disguised

spin. Algie had the measure of his 20 year old opponent although his attacking game let

him down somewhat. Jackson’s day would come again.

Murray Dunn (15) drew attention to himself by beating 18 year old Andy

Wong, the player declared by Leach and Haguenauer to be our best young prospect.

Dunn would have met Frank Paton in the next round but Paton had fallen at

the first hurdle, leaving Dunn a clear run to the quarter-finals. Algie put a stop to his

chances of going any further but the two had a great match with Dunn hitting tremendously

hard and with confidence.

The championships were a major challenge for first time hosts, Wairarapa,

who appear to have done a remarkable job despite accommodation difficulties. Their

souvenir programme with its eighty pages and rich variety of articles surpassed anything

done before.

Inter-Island Contest Hits Rocks

For the first time since 1946 no inter-island contest was played. The irony is that this

was meant to be the year when contests for both men’s and women’s teams would be

held for the first time. Only men had been catered for until now.

The two contests were scheduled separately at two different locations. North Taranaki were

to host the men’s but were unable to meet a condition imposed by the South Island

team that, unless the hosts paid the cost of air travel, they wouldn’t come. The best

North Taranaki could do was offer one quarter of the fare. This was not accepted and,

despite mediation from NZTTA, by the time some sort of compromise was struck it was too

late and the contest was cancelled.

The Waikato Association, scheduled to host the women’s event two months later,

concluded that they were unable to meet the financial burden. Thus the women’s

contest was also cancelled.

Annual General Meeting Plans Ahead

The women’s inter-island event was one of several proposals unveiled at the AGM by

the NZTTA Executive. Setting up an Umpires Association and introducing a junior

inter-Association tournament were others.

|